Distributed Consensus, Atomic Commit and FLP Theorem

Let's see the concept of consensus in distributed systems: what it is, why it is complex, when and if it is possible. We'll see a protocol for achieving atomic commit, and finally we prove the FLP theorem.

In the context of distributed systems, consensus is a key issue. If we have n processes running the same protocol, consensus means that they all have to agree on the same decision.

But in the previous article we saw that processes can fail, in particular they can go into crash or be bizantine. That is why ensuring consensus is not at all easy: how do we get everyone to agree if some trial always dies? Can we continue even if a percentage of trials die? How do we notify resurrected dead trials of previous decisions? Does it need to be done? What happens if too many nodes fail?

In short, there are a number of questions we can’t answer right now, but as we proceed with this article and subsequent ones, we will have a clearer idea and be able to give ourselves answers.

The consensus is all over the place: when two clients edit a Google document together, there is some consensus protocol underneath; when we use services to replicate databases, there is some consensus protocol; when we surf around the Internet and content is served to us by a CDN, it runs some consensus protocol.

Okay, nice talk, but what does consensus mean in practice?

Here, an example of a consensus problem is the so-called atomic commit, which is a decision that we want to think of as atomic, but is actually composed of several operations. For example, if we are several people and we want to choose one pizza to order we might all propose one type, but in the end what is important is to arrive at a single decision to communicate to the waiter.

Our order then becomes atomic in the sense that the various individual proposals should no longer matter because there is one correct final decision to which everyone has said yes.

This problem has its own formalization: let’s see it.

Atomic commit

All nodes must agree on the same decision.

This is not possible if the system is asynchronous and processes can fail (we will see why later).

There is a coordinating process.

There are several participating processes.

The goal is to decide something about a transaction: commit or abort.

In addition, we have some properties:

- AC1: all processes that reach a decision, reach the same decision.

- AC2: a process cannot change its mind.

- AC3: commit can only be reached if all processes have voted yes.

- AC4: if there are no failures and all processes have voted yes, then the decision must be commit.

- AC5: after a resolution of failures, the transaction must be completed (recovery).

Fine. Is there a protocol for resolving atomic commit? Yes, and it is the two-phase-commit.

2-phase-commit (2PC)

The protocol works like this:

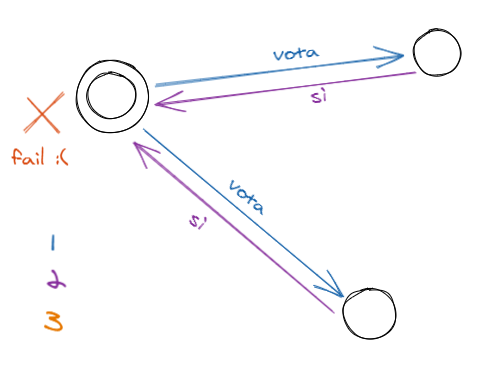

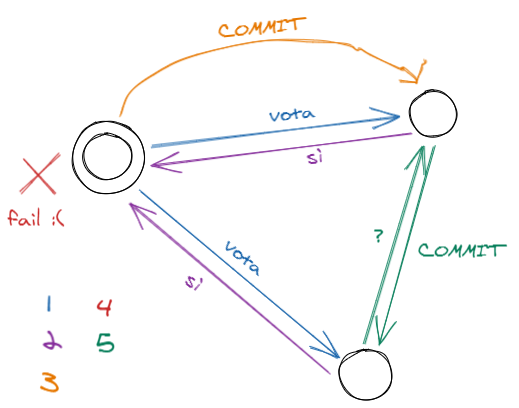

- The coordinator sends a vote request to all participants.

- Each participant responds to the coordinator with yes or no.

- If all responses are yes, then it sends everyone a commit; otherwise it sends abort.

- Each participant updates its status with that received from the coordinator.

We can see that if the participant votes no, he can already put himself in abort status, because he already knows that will be the final decision.

Well, nice.

What are the possible problems of this protocol?

- If the coordinator fails, the protocol does not go forward.

- If the nodes fail, we may never reach the commit.

To deal with the problem of coordinator weakness as a central point of failure, we can use the cooperative termination protocol, which is a stratagem to make the protocol terminate in a certain situation.

Cooperative termination protocol

Let’s imagine a situation where the coordinator fails before sending the final decision.

The protocol will not terminate because all nodes will never receive the final decision because the coordinator fails before sending it. There is little to be done here. Let’s examine a case where something can be done.

In this situation, the coordinator fails immediately after sending the final decision to at least one node; we then realize that something can be done: all that is needed is for this lucky node to propagate the decision to all its little friends.

To be precise, this propagation happens on request: if a node is in the state of uncertainty and receives nothing from the coordinator, after a certain time it can knock on the other participants and ask if any of them already has the final answer.

With the cooperative termination protocol we certainly do not solve the problems permanently, but at least we give the protocol a few more chances to terminate successfully.

Recovery

We have often talked about crash type failures. Okay, what does a node do when it wakes up? Does it know who it is? Does it have to ask something of the other processes? Does it have to vote again?

All these questions can be self-answered by the node if it maintains its own local log of everything it learns. This log is called a DTlog, and it is used by nodes to reconstruct voting states when they wake up after a crash.

There are minimum compile rules, meaning each node must write at least this much information:

- The coordinator writes “start-2pc” at the beginning of the protocol.

- When a participant votes yes, it must write it before sending the message.

- When a participant votes no, he/she must write it down.

- When a participant receives a decision, he/she writes it down.

- If the coordinator chooses commit, he/she must write it down before sending messages.

- If the coordinator chooses abort, he must write it down.

Simple, right?

We conclude this article by finally explaining why I say here and in the previous article that consensus cannot be reached under certain conditions.

FLP Theorem

There is a beautiful theorem named after its inventors-Michael Fischer, Nancy Lynch, and Michael Patterson. This theorem is also called FLP impossibility result, and essentially says that:

In an asynchronous distributed system where crash-type failures are possible, it is not possible to have a deterministic protocol for reaching consensus.

This seems a little strange, since earlier we saw a simple deterministic protocol to achieve atomic commit, which is a form of consensus; we also showed that in certain situations the protocol can terminate even if there is some crash. So why do we say that consensus cannot be achieved?

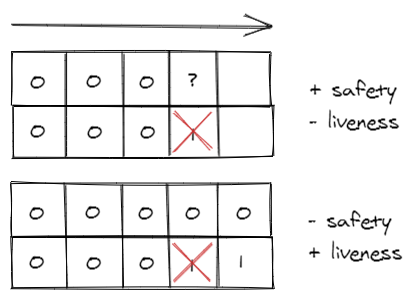

Well, because you have to understand that these three people defined the concept of consensus with two properties: safety and liveness. Specifically, when we say “reach consensus” we are implicitly saying that we do so in a safe and live way.

In simple words, these two properties mean:

- Safety: the choice made by the protocol is correct, in the sense that it cannot be proven (at a later time) that the correct decision was another.

- Liveness: the protocol always allows a decision (whether correct or incorrect) to be reached.

For example, 2PC is trivially not live, because if the coordinator fails we might not be able to decide anything; it is instead safe because once all the yes are collected, the correct decision must necessarily be commit.

This is why we often read a more explicit version of the FLP Theorem, namely:

In an asynchronous distributed system where crash-type failures are possible, it is not possible to have a deterministic consensus protocol that is safe and live.

We can convince ourselves of this with a small demonstration: suppose we have a system in which two nodes must always agree on a value: so if one node changes from 0 to 1, the other must also.

If we admit the possibility of having even one crash, two things can happen:

- In the first case, one process changes its value but fails before the other can notice; at this point the living process remains locked because it does not know which is the correct choice. We then sacrifice liveness to remain safe.

- In the second case the process fails before the other can realize it, but this one doesn’t care and keeps his value in the name of progress; too bad that after a while the dead man resurrects and they find they are at odds. We sacrificed safety to stay alive.

Nice huh?

Conclusion

With this second part, we addressed the issue of consensus and understood why it is critical; we asked and answered questions and realized that if nodes die and we are in an asynchronous system, it is difficult to achieve consensus in both safe and live ways.

For example, the Proof-of-Work mechanism that Bitcoin uses to determine consensus on a block is both non-safe and non-live, but it succeeds in both with high probability (it is in fact non-deterministic, but probabilistic).

In the next article we will look at Paxos, which instead is safe but not live.

Posts in this series

- Paxos: A Distributed Consensus Protocol

- Distributed Consensus, Atomic Commit and FLP Theorem

- Basics of Distributed Systems Theory