Paxos: a distributed consensus protocol

Let's look at Paxos: a beautiful and fundamental safe, but not live, distributed consensus protocol. Let's see how it works, what the main elements are, and have some examples.

In the last article we looked at the topic of consensus and understood why it is important complex; we looked at the concepts of safety and liveness, gave some examples, and then left off by saying that in the next article (this one) we would look at Paxos.

Paxos is a protocol for reaching consensus in distributed systems; it is safe but not live, and it does not tolerate byzantine nodes. It was invented by that crazy genius Leslie Lamport and given to the world in a paper titled The Part-Time Parliament, in the form of a fake archaeological survey of an invented Greek island called Paxos (which then really exists).

At the beginning of that paper, Lamport writes:

Recent archaeological discoveries on the island of Paxos reveal that the parliament functioned despite the “passing” propensity of its part-time legislators. Legislators maintained consistent copies of parliamentary records, despite their frequent escapes from the chamber and to the fact that their messages were easily forgotten. The Paxos parliamentary protocol provides us with a new way of implementing the state-machine approach to designing distributed systems.

Basically Leslie came up with a fake archaeological research paper on a nonexistent civilization that had a particular system in which politicians worked part-time. No one understood anything about that paper, so much so that a while later Lamport published Paxos Made Simple, and no one understood anything about it either.

This - in part - is one reason why Paxos is so feared and misunderstood. In this article we try to understand it.

How Paxos works

Paxos is a protocol for reaching consensus on a value, and maintaining it as long as the protocol is running. The nodes participating in Paxos can have different roles, and the execution of the protocol is divided into shifts. Let’s take a closer look.

Roles of processes

We have three types of nodes:

- Proposer: chooses a value to vote on and proposes it to everyone.

- Acceptor: receives the proposal from the proposer, votes on it or not.

- Learner: stores the value voted by the majority.

Okay, this is a very broad description; now we will take a closer look at how they interact with each other.

Protocol execution

Orientatively, Paxos works like this:

- A proposer starts a voting round, sending everyone a message we call $prepare$.

- The acceptors who receive it can respond with a $promise$, thus committing to vote for that round.

- The proposer chooses a value and sends it to everyone with an $accept$.

- The acceptors tell the learners to learn that value with a $learn$.

It is actually slightly more complicated than that, in fact:

- The messages contain data.

- The proposer chooses the value based on a rule.

- For the value to be chosen there must be a quorum of acceptors.

Okay, let’s look at an example.

Example 1

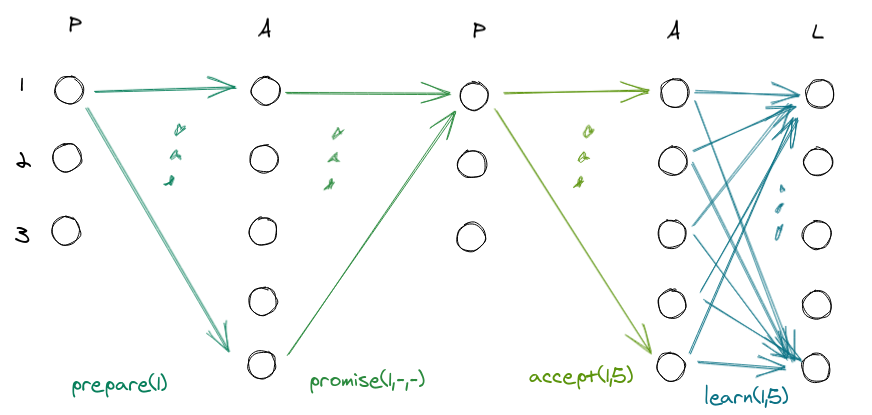

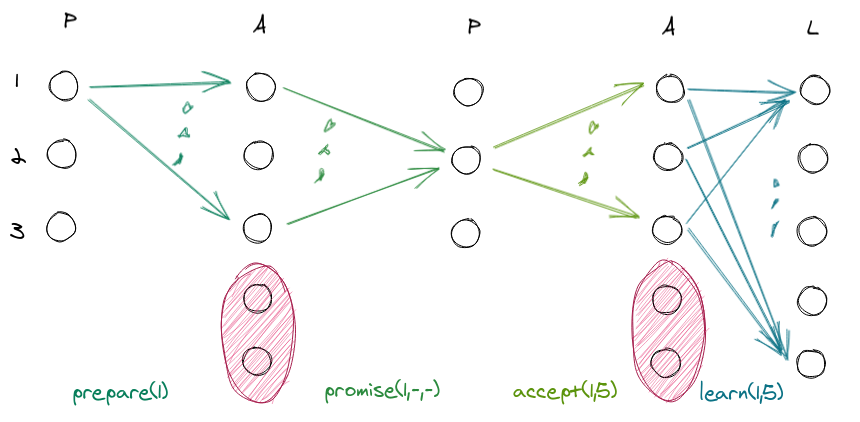

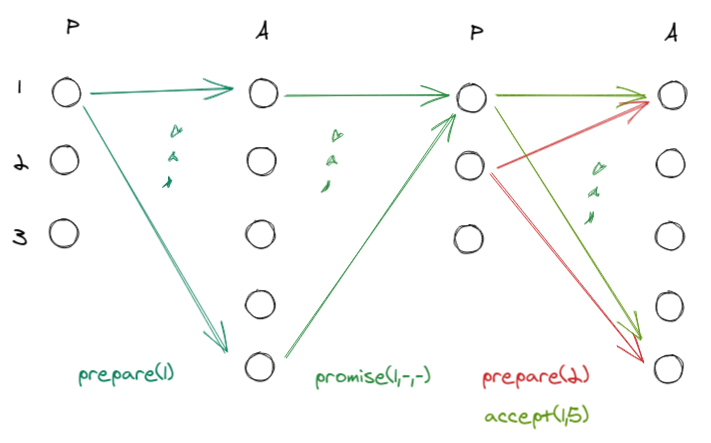

Let us first understand what is in the image:

- P, A, L are Proposer, Acceptor, Learner respectively.

- We have 3 proposer and 5 acceptor, 5 learner.

- The graph shows the what happens over time between proposer, acceptor, learner.

- Arrows represent messages exchanged between nodes.

- The dots represent a set of messages (not drawn so as not to make a graphic delirium)

- Each proposer has an associated shift:

- Proposer 1 -> shift 1

- Proposer 2 -> shift 2

- Proposer 3 -> turn 3

Each proposer actually has more than one shift associated with it, for example:

- Proposer 1 -> turn 1,4,7,…

- Proposer 2 -> turns 2,5,8,…

- Proposer 3 -> turns 3,6,9,…

That said, let’s see what happens in the example:

- The proposer 1 starts the protocol and sends everyone a $prepare(1)$ specifying the turn.

- The acceptors respond with a $promise(1,-,-)$, which contains:

- Shift.

- Last round attended (none so far).

- Last voted value (none for now).

- The proposer receives more than half of the $promises$, and can then send everyone an $accept(1,5)$, specifying the value (5) to be voted for round (1).

- The acceptors vote by sending the learners their intention with $learn(1,5)$.

Nice.

Let’s take a little break by seeing the format and meaning of the messages a little better.

Messages in Paxos

| Message | Who | To Whom | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| $prepare(r)$ | Proposer | Acceptor | Hey guys, I started a vote! The current round (round) is $r$. |

| $promise(r,lr,lv)$ | Acceptor | Proposer | Dear proposer, I solemnly promise to participate in your round. I also inform you that the last time I voted was for the round $lr$, and I voted $lv$. I also pledge not to participate in any $r’$ rounds older than yours ($r’<r$). |

| $accept(r,v)$ | Proposer | Acceptor | Ok, the value you need to vote for round $r$ is $v$. |

| $learn(r,v)$ | Acceptor | Learner | I vote the value $v$ in round $r$. Let it be written in the sacred records. |

Before sending an $accept(r,v)$, the proposer waits to receive at least $\frac{n}{2}+1$ $promise(r,lr,lv)$. where $n$ is the number of nodes. This quantity is called the quorum ($q$).

The same check is done by the learners before storing the value sent to them by the acceptors.

Example 2

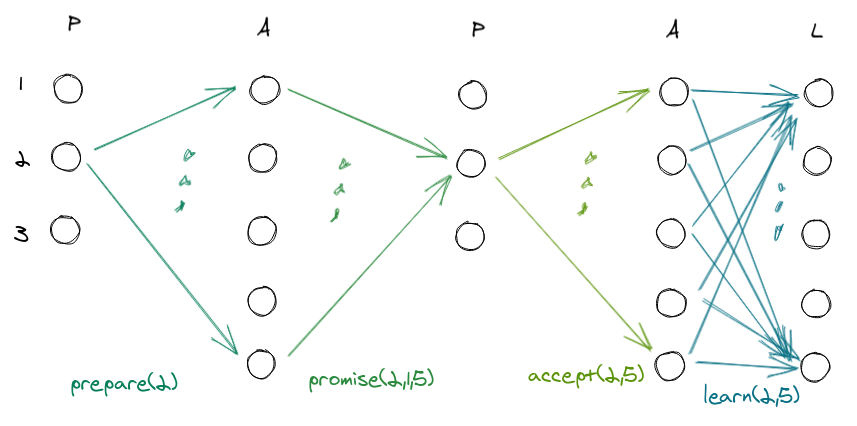

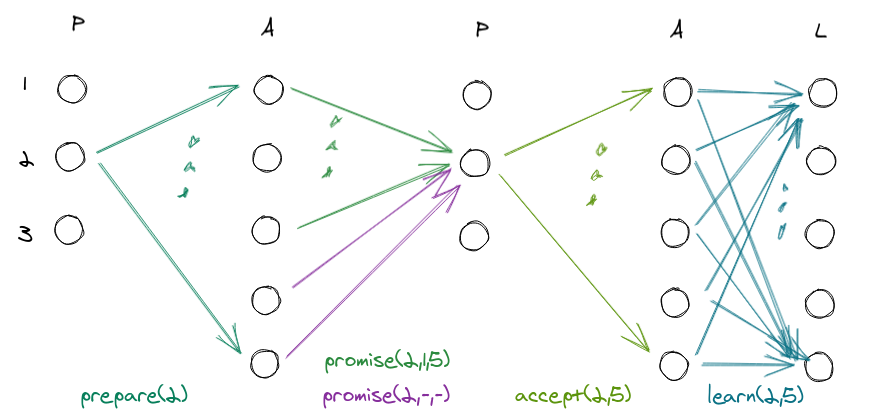

Suppose we continue from where we left off in the previous example. The vote is successful, and the second proposer starts a new round.

Let’s reason:

- Proposer 2 starts a new round with $r=2$.

- The acceptors receive the $prepare(2)$ and decide to take part in that round, then respond with a $promise(2,1,5)$, i.e., they indicate to take part in round $2$, and inform that the last time they voted was for round $1$ and they voted $5$.

- The proposer receives at least half of the responses proposing a value, which must perforce be $5$ (surprise, I will explain shortly).

- The acceptors receive the proposition and send the learn to the learners.

Again in this example everything goes well:

- No nodes fail.

- No nodes failed in the previous round.

In this example we also saw a strange thing:

Why does the proposer have to choose 5? Can’t he choose another value? He is a proposer, he has to propose a value, so why can’t he make it up?

To answer this question, let’s remember what Paxos is for:

- Reach consensus on a value.

- Maintain the value achieved until the end of the protocol.

And we realize that the consensus value was chosen in the previous round, and it is indeed $5$, so the proposer maintains that value. In fact, only in the first round does the proposer really propne a value.

Somewhat more formally, after the proposer receives at least half of the $promises$, he applies this rule:

- If in all $promises$ there is $lr=-$, it means that this is the first round, so it arbitrarily chooses $v$.

- Otherwise, it chooses $value[max(lr)]$, that is, the value $lv$ associated with the last round.

Regarding the last case there is to say that because of the way the protocol works, there is a guarantee that this value will always be unique, i.e., it is not possible for there to be more than one voted value in the same round.

Now let’s look at an example where something splits.

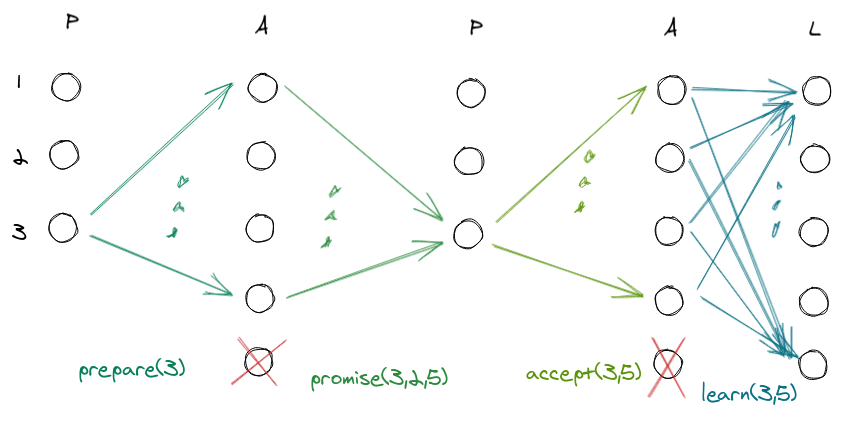

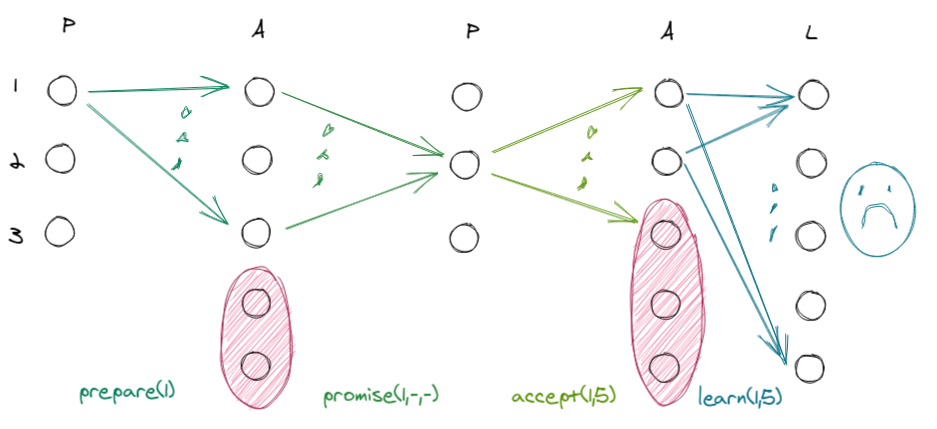

Example 3

Here an acceptor dies and remains dead for the entire turn. The vote is still successful because there is a quorum. The interesting thing happens in the next turn, when this dead acceptor wakes up; let’s see what he says.

In turn 3 he was dead, in turn 4 he awakens and participates in the vote. At this point he will be the only node that in the $promise$ will say he last voted in another round, but nothing changes:

- The proposer chooses the value associated with the last round, i.e. in this case $max(lr)=3 \rightarrow lv=5$.

- The dead node (in this case) already has the consensus value (5), because it was alive when it was reached, and it will not be able to change.

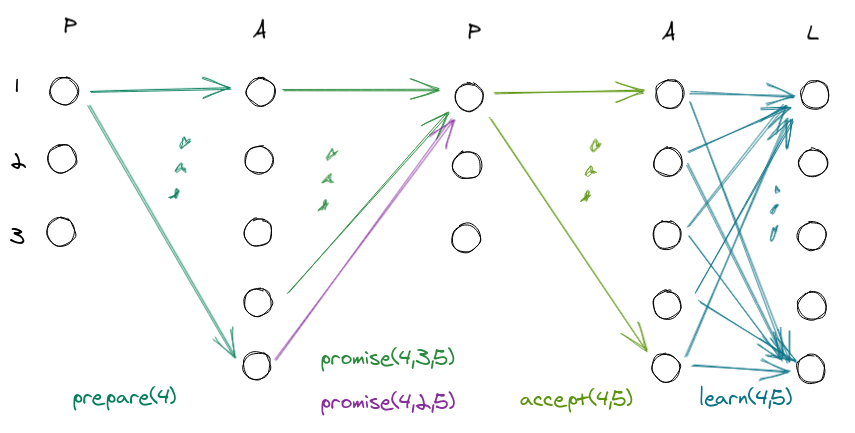

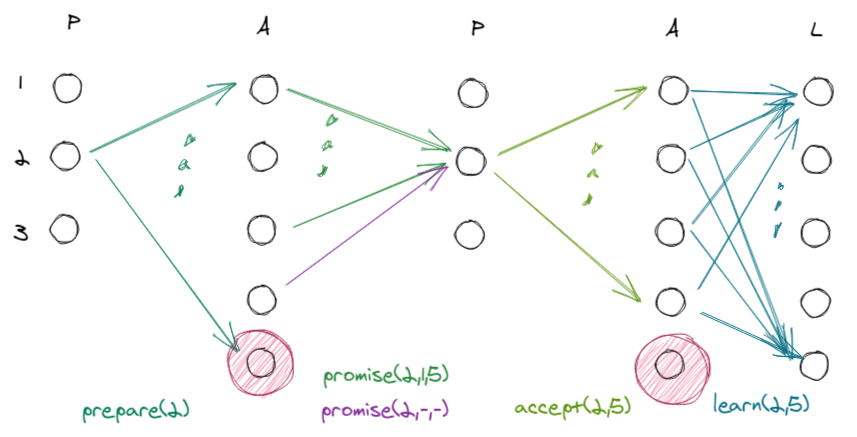

Example 4

Let us now see what happens when there are dead nodes in the first round.

Two acceptors fail and stay down for the entire turn. The others quietly vote the $5 value. A quorum is there, and all is well.

On the next round they wake up and participate in the voting, and we are not surprised to see that all is well anyway:

- These acceptors are the only ones who send a $promise(2,-,-)$, that is, saying that they have not yet voted.

- The value chosen is $5$ anyway, because $max(lr)=1 \rightarrow lv=5$

Funny, isn’t it?

Example 5

Now that we’ve gotten good, let’s look at a slightly more broken case.

Two acceptors die before receiving $prepare$, and another dies before receiving $accept$. There is no longer a quorum, so the value $5$ is not written.

On the next round only one failed acceptor remains, all is well, and the chosen value is finally recorded.

Perfect.

Safety

We said at the beginning that Paxos is safe but not live. Let us see why it is safe, that is, that whatever choice the protocol makes is correct; in other words, it is not possible that in a round $r’>r$ it turns out that the acceptor value chosen in round $r$ is wrong.

As a prerequisite, we must first be convinced that once we successfully choose and vote for a value, in each subsequent round the value will never be different. It is fairly easy to convince ourselves of this, thanks to the rule that the proposer uses to choose the value: once the $promises$ needed to form a quorum are received, the proposer chooses the value associated with the most recent round. Therefore, once a value $v$ has been chosen in round $i$, in each round $r’>r$ the proposer will always choose the same value $v$, ergo it is not possible in a round $r’>r$ to have a value $v’ \ne v$.

At this point if we fix $j=max(lr)$ we have two cases to reason about:

No vote

If $j=-$ it means that no one voted; more formally, it means that $\forall j \le i-1$ where $i$ is the current round, there were no votes.

In this case it is safe to do an $accept(i,v)$.

Someone voted

If $j\ge1$ means that someone voted. If $i$ is the current round (and $j\le i$), the nodes that voted in this round have sent a $promise(i,lr,lv)$ and have thus also promised to ignore any vacant messages referring to rounds $i’<i$.

This means that $\not\exists \space v’\ne v$ voted in the time window $[j;i-1]$, so it is safe to make an $accept(i,v)$.

Put simply:

- Since the proposer chooses values according to that rule, there is a guarantee that once a value is chosen, the consensus on that value is maintained from that point on.

- Since $promises$ also have the meaning of ignoring any votes still open for previous rounds, you are guaranteed that once a value is chosen in one round, it does not change during another round.

Lack of liveness

It is easy to see that Paxos is not live, i.e., that there are instances where the protocol never makes a choice. The key is precisely in the meaning of $promise(r,lr,lv)$, in which the acceptor promises the proposer to vote for round $r$, but also to ignore all messages related to rounds $r’<r$.

In fact, this can happen:

What happens if a proposer sends a $prepare(r)$ during the vote for the previous round?

The protocol does not say that proposers must wait until the end of a previous round, so they can behave as they wish.

In this case, a bad proposer sends $prepare(2)$ before proposer 1 can send a $accept(1,5)$, and before the acceptors can then vote on the value. The acceptors will then start working for round 2 and ignore the messages from round 1.

This dynamic can go on indefinitely (even at other stages of the protocol), thus resulting in the absence of liveness.

Paxos with coordinator

A possible variant of Paxos is to add a coordinator that handles all rounds: it basically acts as a proxy between proposers and acceptors, thus becoming the special proposer for each round.

This avoids those scenarios where the proposers spite each other, which results in a lack of liveness.

Of course, electing a coordinator (leader election) is itself a form of consensus, so we bite each other’s tails. What is generally done is to use a weak protocol to choose the leader, i.e., a protocol that does not have to be safe, but that suits us anyway in relation to our goal, i.e., it certainly elevates a proposer to coordinator.

Role flexibility

Two final words about Paxos concern roles. Earlier we saw that there are the roles of:

- Proposer.

- Acceptor.

- Learner.

If we allow for the variation seen just now, we also have a Coordinator.

Fine, but we must say that in Paxos the roles are flexible, that is, at different times of the turn a node can also take on other roles. For example, the special proposer of a certain turn, may also be one of the acceptors, and surely he will also be a learner.

Conclusion

We looked at Paxos and framed it within the larger context of consensus in distributed systems. We’ve seen how it works, what the roles of the nodes are, and what messages are exchanged and why; we’ve given some examples, and seen why it is safe but not live.

There are some extensions to Paxos, like the one with the coordinator, but also interesting stuff like Multi-Paxos, which is an environment in which multiple instances of Paxos are run, for example to handle consensus on a sequence of values.

Fast Paxos is based on Multi-Paxos: a protocol that introduces optimization in the first round, at the cost of some failure tolerance and some confusion.

Posts in this series

- Paxos: A Distributed Consensus Protocol

- Distributed Consensus, Atomic Commit and FLP Theorem

- Basics of Distributed Systems Theory